by Peter Matusov

Have you ever spent any time on Interstate 15 between Southern California and Las Vegas? Have you seen these jeeps or Toyotas or side-by-sides or motorcycles blasting by, raising clouds of dust, and leaving you behind in a hopeless two-lane-each-way, bumper-to-bumper traffic?

I went one step further and once made a New Year resolution NEVER to return to Interstate 15 (with a purpose of interstate travel). That resolution lasted all of two months, and I was back - telling myself things like "one time only," or "that's because there's no traffic," or something stupid like that. The truth is, you can't avoid it - just like trying to avoid toll highways in France. Can you bypass it? Yes, you can. But it'll cost you another day, on top of what you've already wasted in traffic.

The other freeways leaving mountain-rimmed Southern California are not always better. Only Interstate 8 is good for you - till you get down to the “Sea Level" sign. The Five dumps you into the Central Valley, with the same deranged traffic and smell of cow shit. The Ten and Forty... Hold on, both of those also cross Mojave Desert.

Mojave Desert

That desert, unlike, say, County or State boundaries, has some geophysical reasons to be called a name. It is cut abruptly on the East by Colorado River - enough for the flora and fauna to be different on the other side of whatever shallow creek is left of it close to Mexican border. According to Wikipedia, it is hemmed on the North by Garlock fault - which puzzles me, because since the same Wikipedia lumps the Death Valley with the Mojave Desert. The mighty San Andreas Fault roughly outlines Mojave Desert on the West. The southern boundary of Mojave is a bit more fluid, stretching to the northern reaches of Anza-Borrego (Colorado Desert) according to some sources, and cut off by Interstate 40 - to the others. A backseat observer on the Interstate 10 won't be able to tell the difference in nature between the left or right shoulder, so it must be stretching pretty far south.

Of the most-prominent North American deserts, the Mojave Desert is also labelled to be the smallest of the rest, including Sonoran Desert, Great Basin, and Chihuahuan Desert. It may sound disparaging, until one looks at the numbers: its (Wiki-declared) area is about 54 thousand square miles, or 140 thousand square kilometers. It makes it larger than the land mass of Illinois or Iowa, for instance, and larger than any East Coast state except for Georgia (and that just by a little). For the statistically minded non-North Americans, it is about the size of Tajikistan - which is a bit of a vague reference. Mojave Desert is much larger than Greece.

Death Valley (enormous by itself) makes a small part of Mojave Desert. Besides desert tortoise and bighorn sheep and burros and scorpions, the desert is also home for some enormous American military bases, including China Lake Naval Weapons range, Fort Irwin, Edwards Air Force base, and others. Cities? We have them in Mojave, including California City, Victorville, and Barstow in Golden State, Las Vegas, Nevada, and St. George in Utah.

There are sand dunes, dry lakes, underwater rivers, and mountain ranges within Mojave - but most of them stay out of sight for a bored-brainless backseat traveler in a car plodding away on Interstate 15. Definitely, out of sight of a driver of the same car, foaming at the mouth at the noble attempt of a tanker truck full of diesel fuel pass a flatbed with 40 tons of coiled steel on Baker grade.

And that's when we glimpse those two-cycle lightweights that pass us happily in the dirt, and marvel about what it would be like to ditch the pavement.

Mojave Road

The sheer enormity of Mojave Desert makes you wonder about the earlier settlers of the West who found a myriad of ways to cross this vast empire. From Southern Utah to Mexican border, their last drink of fresh water was from Colorado river - save from a spring here and there or the riverlets of the West Coast, they would never taste it again. The Native American desert dwellers traced the path in the desert from one watering hole to the next. The Mojaves (as the tribes were known) have been proud, but peaceful people, and rather welcomed the newcomers from Europe - first, Spaniards traveling from mainland Mexico towards the Pacific. Around 1830, a large section of today's route west of Colorado River became a part of Old Spanish Trail to California. In 1848, in the aftermath of the Mexican-American war, Mexico ceded the land to the United States.

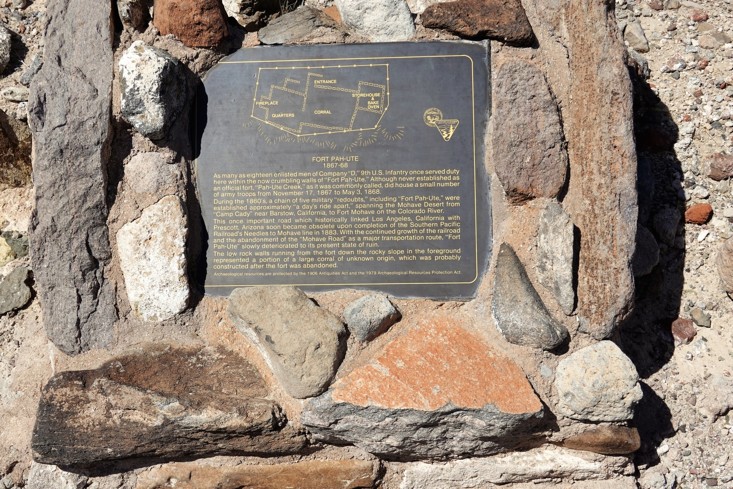

The 1849 brought about California Gold Rush, and Old Spanish Trail offered an alternative to the fate of Donner Party in Sierra Nevada - hot, dry, dusty, but without the bitter cold at higher elevations. The new settlers weren't kind to the Mojaves, and the Indians retaliated - which set off a Mohave War of 1858-1859. The U.S. Government then built a few forts - from Fort Mojave mostly on the left bank of Colorado river to Fort Paiute to Camp Cady not far from the present-day Barstow, - and maintained the army presence for protection of settlers and travelers from Mojave, Paiute, and other Native American tribes until the early 1870s.

In the late 1800s, the road also served the silver and gold mining development in Arizona. The cattle ranchers started arriving into the eastern Mojave Desert in mid 1880s, mostly using Mojave Road. Once Mojave Desert opened to homesteading in 1910, a few towns sprang up including Lanfair - with its own post office from 1912 to 1927. Ranching in the desert is never easy, so, despite still enormous private land ownership in Lanfair Valley in our days, there were no permanent residents in Lanfair since 1946.

With the proliferation of the U.S. highways in the desert, Mojave Road gradually fell out of use. Some sections of it realigned with newer or larger roads, and some parts fell into disrepair and were forgotten. It took love and perseverance of a former U.S. Marine stationed at Twentynine Palms, Dennis Casebier, to dig up old archives (before the age of the Internet!), and retrace the original route of Mojave Road. He formed a group - "Friends of the Mojave Road" - to work with the BLM on the status and condition of the road, and published "Mojave Road Guide", which endured four editions and is considered a Bible of the road. It is indeed a fantastic read with a wealth of information - both historical and geographical. The book is accompanied by the map of the road, which, along with the by-the-mile narrative of the book, is completely sufficient for the "GPS-denied" navigation along the entire almost 150-mile stretch.

It would be an over-generalization to state that the road could be driven in a two-wheel-drive pickup truck, or an all-wheel-drive crossover wagon, or that it absolutely requires a burly 4x4 with a large ground clearance. Whatever used to be a hard-packed dirt road may turn into a quagmire after recent rainstorms, or deep sand after a long dry spell. Like the roads in Death Valley, it crosses a few lava beds with sharp rocks requiring constant attention.

Also, while very infrequently technical, Mojave Road passes through the very scarcely populated desert - even when you think you're only 30 miles, say, from Interstate 15 or 40, remember from your last highway trip to Vegas or Grand Canyon that there isn't much on it.

Day 1 - Avi Casino to Carruthers Canyon

The meeting is set at 9 in the morning at the parking lot of Avi Resort and Casino, tucked tight in the very southernmost corner of Nevada, on the former western grounds of Fort Mojave. We meet at the gas station first and move to the shade of the grand entrance to the casino. Five Grenadiers - all different in color and equipment - are loaded and ready to head west. Some time is spent tweaking ham and GMRS radios to ensure communication, and we're off to the dirt, after a few miles on pavement. We air down once we leave the blacktop - each to his own limit of ambition and desire for comfort. Aaron Shrier is leading the trip, and I volunteer for the tailgunning duties.

Here, Mojave Road wiggles around the California-Nevada border, venturing into either state at times. We see some odd encampments along - like a pair of RVs set up in the shape of a V, with some supplies stacked up high on the far side, and signs discouraging the intrusion by inquisitive passers-by. We make jokes about meth labs and discuss means of putting them out of commission - someone on the radio informs me that C-4 is far cheaper means than a Hellfire missile. The road is mostly sandy, with occasional whoop-de-doos and rocky sections - making us slow down considerably.

Our first stop is at the ruins of Fort Piute; on the way, we pass the remnants of the turkey farm owned by the family of George and Virginia Irwin in the middle of 1940s. The Irwins bravely defended their birds from coyotes and cougars for a couple of years, then gave up and moved away.

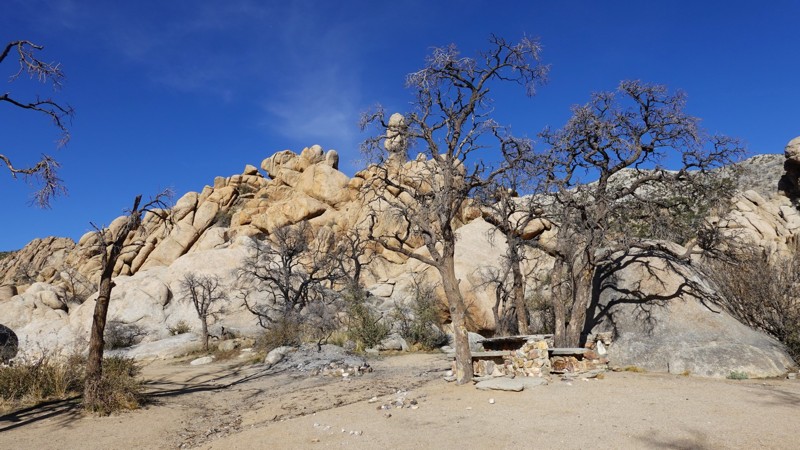

Fort Piute was originally built in 1859 as Fort Beale. It was abandoned with the conclusion of the Civil War, but reoccupied in 1866 to protect the travelers on Mojave Road from the hostile indigenous population and renamed Fort Piute after a solitary water source - Piute (or Pah-ute) Creek nearby. In 1868, it was abandoned again, this time for good. Now, all that is left are the two-foot-high remains of the stone walls of the fort.

In the 1860s, the road continued up through the shallow pass and up the hillside - which was then considered one of the harshest sections of the Mojave trail. Now it is closed to vehicular traffic, so we have to retrace our steps and go around the hill - after a quick lunch near the fort.

The shelf road around the hill is rocky and steep in places. This is where we hear on the radio - "we lost a tire... oh wait, we bent a rim!"

It didn't take long, did it? We stop and assess the situation. The rim is indeed bent - dented a good couple of inches at the lip, and the tire's bead is off its groove. It can't be repaired in place; and the spare tire on this truck appears to proudly sport a locknut supplied by the dealer but without the key. Out of five trucks, three have the same size and make of tires, two - same wheels, and only one with the spare tire that could be fetched without any surprises. Kudos to Alberto, the owner, who took his time to make sure his spare tire can be used in a time of need.

We proceed with the plethora of expensive tools - attempting to remove the damaged wheel using a battery-powered impact wrench, before securing the vehicle on the hillside and jacking up the corner. Back up a step, jam rocks under the wheels, and use the ARB's hydraulic (and very expensive) take on Hi-Lift jack to lift the wheel off the ground.

The wheel is replaced, and the tires are refilled with air to match the spare's air pressure. By this time, we created a bit of a traffic jam on Mojave Road: we are followed by five dudes in a Subaru Outback, and then by three guys in beat-up Tacomas. The Tacoma guys didn't mind the accidental stop at all and kept working on their stash of Coors Light.

Soon after, we drop into Lanfair Valley, and the road meanders between progressively more frequent Joshua trees. The road gradually picks up elevation, and we start seeing occasional junipers as we near a 4500 feet mark. The area looks burned by a brush fire years ago - with many Joshua trees, junipers, and Palo Verde trees still blackened and lifeless.

Aaron points out the New York Mountains to our right, and soon we turn north, and uphill, towards Caruther’s Canyon. Soon, we arrive at the end of the trail, close to 5800 feet in elevation, with a great established campsite with a fire ring, concrete benches and a table, and surrounded by scenic rock formations on all sides. It is late afternoon, and it seems like the most reasonable place to camp.

We trade places a few times - people sleeping in their vehicles have lesser demands of the surface, - and set up camp. Gin and tonic are produced from the fridge. Soon, with the tents all set and dinner cooked, the campfire is roaring, and yarn is being spun.

Tally for the day: 3 miles on pavement (157 miles – for me) and 39 miles on dirt.

* * *

Day 2 – Caruther’s Canyon to Seventeen Mile Point

After a shot of nuclear coffee (try a 6-cup Moka Pot split between two cups) and morning sandwiches, Aaron and I decide to give unbending the wheel a try. The nearly two-inch-deep dent unfortunately landed on the spot where the tire pressure sensor is – so simply whacking it with a sledgehammer is somewhat out of question. Instead, we use Aaron’s Hi-Lift jack – using the hub borehole in the wheel flange for the base, and jack lifting lip – for the rim. It takes us some serious effort – between the jack static pressure and some sledgehammer beating along the way, the rim seems to be getting straighter. The tire bead is re-seated (jumping on the rim proved better than running a ratchet strap along the circumference of the tire and blasting the CO2 from a Powertank), yet it is still leaking air.

After exhausting the options with the Hi-Lift, we try the factory Grenadier bottle jack with some short lifting straps and pieces of lumber. Again, the combination of static pressure with sledgehammer yields some improvement – the tire still loses air but can actually be used. The tire owner takes no part in the process and seems incredulous that we’d waste time and effort on fixing a ruined wheel. Oh well – to each his own.

Wrestling with the bent wheel takes us nearly two hours, and by the time we call it quits everyone is packed up and ready to go. We retrace our steps downhill from Caruther’s Canyon back to Mojave Road. From time to time, we deviate from Mojave route to Cedar Canyon Road – a pretty wide and flat desert throughfare, but we can’t miss a badly-eroded and steep downhill stretch just to spice up our game.

Soon after, we pull over to visit Rock Spring – one of very few water sources communicated by Mojave people to the newcomers. Officially, water at the site was first discovered in 1853 by A.W. Whipple, at the time a topographical engineer in the U.S. Army, during an expedition he led to establish a rail route to Pacific Coast along the 35th parallel. Soon, Rock Spring became yet another military post along Mojave Road – the spot started housing a guard sometime in 1860 and was manned on and off until 1863. On December 30 of 1866 (what accuracy!), Camp Rock Springs was established. The life at the post was very harsh, supplies – scarce and insanely expensive. By 1867, the spring nearby dried off, and it prompted the Secretary of War to order a shutdown of the camp. By 1868 it was practically abandoned.

Today just a lonely jeep is parked nearby with its occupants enjoying mid-morning sun. Our next stop – barely a mile away, but off the main route – is Government Holes.

This was a site of a successful water well, first drilled by Phineas Banning in 1859, then enlarged a year later by the soldiers of the U.S. Army. It served the settlers of Lanfair Valley and passers-by on Mojave Road, as both water source and place to rest. Scarcity of water and shade in the Mojave Desert led to several well-publicized conflicts – the last being a 1925 shootout between two Mojave regulars, likely to have a woman involved, and leading to the demise of both shooters. Nowadays, there is still a working windmill, and a plastic water storage tank in place of the old one made of corrugated steel. We didn’t find any water.

After the visit to the Government Holes, we continue somewhat downhill along Cedar Canyon Road towards the crossing of the paved Kelso-Cima Road. Soon, we can see the majestic Kelso Dunes about 20 miles south of us. The road here passes a dense Cima Joshua Tree Forest and offers a gorgeous view of the valley (which is frequently photographed in publications about Mojave Desert). My view as a tailgunner is somewhat muted by the cloud of dust raised by my friends ahead.

My Grenadier’s odometer turns over the 28 thousand mile mark; we cross an old powerline road and stop by Marl Springs.

Camp Marl Springs was a fort situated practically at mid-point between Fort Mojave and Camp Cady. It was a very desired destination – between a 19-mile trek across the desert valley from Rock Springs and a 17-mile section named Devil’s Playground crossing a fairly young lava bed. Known forever to Mojave natives, the spring first found by a newcomer in 1852. John Brown, a ferry owner from Fort Mojave, was very happy to get his hands on drinking water. The site was also visited and documented in 1854 by Whipple Expedition.

By 1860, Piute Indians were attacking the settlers, and an Army post was established in 1863. The fort was surrounded by hostile natives four years later, and only three soldiers met the rescue party with their scalps intact after a 24-hour siege. Camp Marl Springs was abandoned in May of 1868.

We find a missing plaque, remnants of a corral, and an empty basin with water trickling into it from a steel pipe.

About three miles later, Aaron stops our little convoy by another famous Mojave Road landmark – The Mailbox. Occasionally dubbed as the most remote mailbox in the United States, it was installed by the Friends of the Mojave Road in 1983. Inside, there’s a logbook that every traveler on the Road is expected to sign; we delegate 12-year-old Jonah to make an entry for all of us. Behind the mailbox there’s a collection of plastic frogs, growing by the year – this place reminded me of a marble bath in Death Valley.

Closer to Kelbaker Road, we part ways with the wounded Grenadier due to the potential health issues with the owner’s son and plow on. The departing crew leaves Alberto with the mangled spare tire - hope we don't have any tire issues.

The road now is flanked on the right with a tall and seemingly very young lava bed with a few round promontories – Cinder Cones Lava Bed. National Park Service will tell you that there are 32 active volcanoes in the area – the most-recent volcanic activity happened as recently as 8-10 thousand years ago. Aaron – jokingly or seriously – mentions the official advice to leave the area immediately if the ground becomes very hot.

We continue for a good part of an hour, with paved Kelbaker Road close by on our left, cross it, and find ourselves a campsite in the fold of the Seventeen Mile Point Mountain. This rather lonely peak was given this name by the members of the U.S. Army survey in 1866 and 1867, who found that it is nearly 17 miles away from both Soda Springs on the west and Marl Springs on the east. A mining camp existed near Seventeen Mile Point in the early 1900s, but all the traces of it are gone.

It is hard to find oneself a place to camp in a half a square mile of flat space! We simply roll closer to the mountainside, staying just enough away not to be hit by a wayward rolling rock, and set up camp. Later in the evening, we watch the lights of traffic on Interstate 15 far away and enjoy the thought that we aren't part of it.

Tally for the day: 52 miles, all on dirt.

* * *

Day 3 - Seventeen Mile Point to Afton Canyon (38 miles + 214 on pavement)

The night is peaceful, but the morning unfolds under clouds.

As we start gently downhill along a sandy road, we are greeted by the sign: "Soda Lake Road Open." It gives me hope that we wouldn't have to slog through stinky corrosive mud. The lake opens up in front of us some ten miles later, with white crust hiding chocolate-colored mud underneath. The main road is very hard, and the sides bear the signs of adventurous (and illegal) four-wheeling shenanigans. Some of them seem to have been pretty serious - somebody got stuck badly, then the recovery vehicle followed suit, then... your guess is as good as mine.

Midway across the lake we stop by the rock pile. It is unclear when this tradition started, but the travelers are expected to bring along the largest rock they care to carry and deposit it in the pile. Some rocks are signed and some are fully painted, so Mojave adventurers take this custom seriously.

Less than a mile away, towards the north, lies Zzyxx, formerly known as Soda Springs. One american radio evangelist preacher, Curtis Howe Springer, proclaimed the waters from the spring near Soda Lake to have healing effects, and established Zzyxx Mineral Springs and Health Spa in 1944. The story has it that he made up the word Zzyxx (pronounced as zai-zicks) as "the last word in healing" (and also the last word in English language). Springer made many claims about his life, education, and skills, most of which were untrue. There were never hot springs on the property, and water in the pools was heated with a boiler.

I found it curious that Casebier's Mojave Road Guide is mostly sympathetic to C.H. Springer, bestowing a Doctor's title to his name despite the fact that Springer had neither medical training, nor any doctorate in any other subject. The Journal of American Medical Association went all out in 1936 to publicly call him a quack lacking any formal education.

By the second half of 1960s, Springer started subdividing the land and collecting money for the parcels - which brought him into the crosshairs of the federal government. The Fed found out that he never had the rights to the land (a technicality stemming from his unused and unproven mining claim), and he was evicted and briefly imprisoned in 1974 - ending the story of the resort, but not the place: in 1973 the name Zzyxx appeared in Hammond Ambassador World Atlas, and Rand McNally Commercial Atlas followed suit three years later.

The Bureau of Land Management really had no plan for how to manage the property after prevailing in courts and evicting the Springers, leading to the decline of the resort. For a number of years, California State University maintained a Desert Study Center using the buildings of the former resort; now it is closed to visitors altogether.

We learn about this from Aaron, who keeps the Mojave Road Guide book at the arm's length in his Grenadier. The mystery behind the green "Zzyxx Rd" sign on Interstate 15 is no longer.

After the five-mile crossing of Soda Lake, we enter the sandy desert - the western-most reaches of the Devil's Playground. The little "dunelets" are all around us, and we enjoy the nice and soft road for a few miles. Soon, we start seeing telltale signs of water nearby - we are getting close to Mojave River briefly coming to the surface in Afton Canyon.

The river was well-known to the native inhabitants of the desert and later documented by Spanish newcomers from the late 1700s to early 1800s. John Fremont, traveling in the desert in 1844, gave it a name Mohahve after having met multiple Mohave native trekking along its course. It had been called Macaby River by the Mormon ranchers in mid-1800s. The river originates on the north-facing slopes of San Bernardino Mountains, and disappears mostly underground on the Mojave desert floor. It resurfaces with a vengeance during strong El Nino years, filling Soda Lake and sometimes even Silver Lake further north to the depth of several feet. In confines of Afton Canyon and deep shade of its steep and high walls, Mojave river waters come to the surface, ranging from a series of shallow puddles to a bumper-deep flow near Afton Canyon campground.

We enter the riverbed close to the Union Pacific railroad bridge through Afton Canyon. The canyon was chosen to be the route of Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad in 1910s - as a mail line connecting Los Angeles with Salt Lake City, Denver, and as far as Chicago. We see a long train coming across the bridge in the distance, and I fail to take a video of it for my grandson hoping to catch another train.

By now, the sun is up and it is getting hot. The bridge offers a good shade for lunch, but we move on into the canyon. Aaron spots a near narrow canyon going south of the main route and wants to explore. We gladly follow, for a short while - the seemingly well-traveled two-track road turns into a side-by-side trail, then into a single-track, and then into a slot canyon. We retrace our steps into the mouth of the canyon and find a spot in a shade for lunch.

After lunch, we reconnect to the main route of the Mojave Road, and keep within very close distance from the railroad tracks almost all the way to another bridge - where we cross the river in its probably deepest spot. The crossing is pretty long, about 200 feet, and the water reaches our Grenadiers' front bumper level - between 18" and two feet. That's not the crossing to be done at speed, so we amble through slowly.

Once we're across the river, we are near the entrance to Afton Canyon campground. This is where our trip officially ends. We watch a couple of four-wheelers continuing west on Mojave Road, air up, and take a short Afton Canyon Road spur towards Interstate 15. None of us needs fuel yet, so we join the craziness of the highway till a gas station in Yermo.

After Yermo, we decide against driving in a convoy. I can't say we part ways - all of us are facing at least 75 miles on I-15 to the nearest route decision point. We hit ugly traffic of weekend returnees from Las Vegas in Victorville; I am in front of the pack and, as long as I am not too far away, relay the traffic conditions to the rest of the group. I lose patience with traffic near Bear Valley Road interchange, and opt for surface streets in Victorville and Hesperia to guide me to California highway 138. From my earlier trip to Utah, I know of a dirt bypass that allows me to completely avoid Interstate 15 and use a few miles of relaxed drive on former U.S. 66 all the way downhill to Devore. There I am down to two ugly options - 15 through Corona or 215 through Riverside, place my bet on Express lane on 15, and drive home - already missing the desert.

Tally for the day: 38 miles on dirt, 188 miles on pavement.

* * *